A controlled trial conducted by Weizmann Institute of Science researchers suggests that these non-nutritive sugar substitutes and sweeteners affect the human gut microbes and may alter glucose metabolism; the effects vary greatly among individuals.

Many governments view sugar as a negative, and over recent years have directed consumers towards artificial substitutes. For years, non-nutritional sweeteners have been considered an ideal alternative to natural sugar as they deliver a similar taste to sugar, minus the calories. However, like sugar, it seems that consuming artificial sweetness may come at a price.

Weizmann Institute of Science researchers conducted a controlled trial published today in Cell. The study suggests that, contrary to previous belief, artificial sweeteners are not inert and affect the human body.

In 2014, the institute conducted a study with mice that showed some non-nutritive sweeteners might contribute to changes in the sugar metabolism they are meant to protect. In the new trial, Prof. Eran Elinav (below right) of Weizmann’s Systems Immunology Department and a team of researchers screened 1400 potential participants, choosing 120 that strictly avoided artificially sweetened foods or drinks.

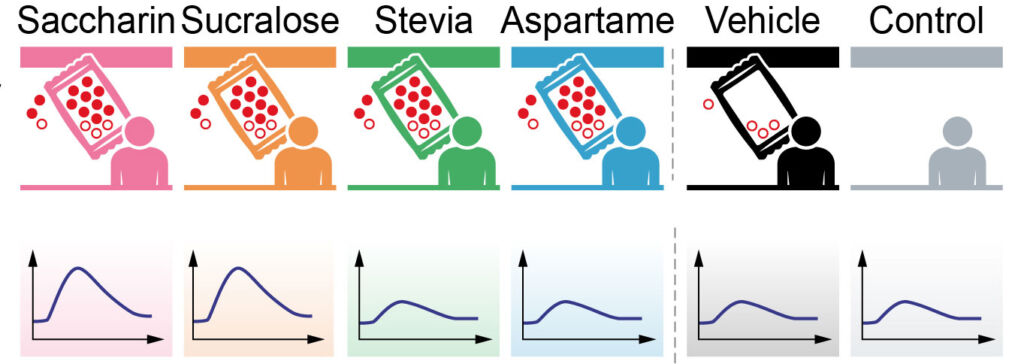

The volunteers were divided into six groups. The researchers provided the participants in four groups with sachets of common non-nutritive sweeteners containing amounts lower than the acceptable daily intake, comprised of one sweetener per group: saccharin, sucralose, and aspartame or stevia. The two other groups served as controls.

Leading the research was Dr Jotham Suez, who was a former student of Elinav’s and who is now the principal investigator at the John Hopkins University School of Medicine. Joining him in the research was Yotam Cohen, who was a graduate student in Elinav’s lab. The two worked in collaboration with Prof. Eran Segal of Weizmann’s Computer Science and Applied Mathematics and Molecular Cell Biology Departments.

Leading the research was Dr Jotham Suez, who was a former student of Elinav’s and who is now the principal investigator at the John Hopkins University School of Medicine. Joining him in the research was Yotam Cohen, who was a graduate student in Elinav’s lab. The two worked in collaboration with Prof. Eran Segal of Weizmann’s Computer Science and Applied Mathematics and Molecular Cell Biology Departments.

The researchers found that two weeks of consuming all four sweeteners altered the composition and function of the microbiome and of the small molecules the gut microbes secrete into people’s blood – each sweetener in its own way.

They also found that two of the sweeteners, saccharin and sucralose, significantly altered glucose tolerance – that is, proper glucose metabolism – in the recipients. Such alterations, in turn, may contribute to metabolic disease. In contrast, no changes were found in the two control groups’ microbiome or glucose tolerance.

The changes induced by the sweeteners in the gut microbes were closely correlated with the alterations in glucose tolerance. “These findings reinforce the view of the microbiome as a hub that integrates the signals coming from the human body’s systems and from external factors such as the food we eat, the medications we take, our lifestyle and physical surroundings,” said Elinav.

To check whether changes in the microbiome were responsible for impaired glucose tolerance, the researchers transplanted gut microbes from more than 40 trial participants into groups of germ-free mice that had never consumed non-nutritive sweeteners.

In each trial group, the transplants were collected from several “top responders” (trial participants featuring the most significant changes in glucose tolerance) and several “bottom responders” (those featuring the least changes in glucose tolerance).

Strikingly, recipient mice showed patterns of glucose tolerance that largely reflected those of the human donors. The mice receiving microbiomes from the “top responders” had the most pronounced alterations in glucose tolerance compared to mouse recipients of microbiomes from “bottom responders” and human controls.

In follow-up experiments, the researchers determined how the different sweeteners affected the abundance of specific species of gut bacteria, their function and the small molecules they secrete into the bloodstream.

“Our trial has shown that non-nutritive sweeteners may impair glucose responses by altering our microbiome, and they do so in a highly personalized manner, that is, by affecting each person in a unique way,” Elinav says. “In fact, this variability was to be expected because of the unique composition of each person’s microbiome.”

He added, “The health implications of the changes that non-nutritive sweeteners may elicit in humans remain to be determined, and they merit new, long-term studies. In the meantime, it’s important to stress that our findings do not imply in any way that sugar consumption, shown to be deleterious to human health in many studies, is superior to non-nutritive sweeteners.”

Read more health news and features here.

![]()

You must be logged in to post a comment.